When we suffer, do we make it worse by thinking about it? This question sits at the heart of how we understand the very nature of human pain–and points toward ancient wisdom we’ve forgotten in our modern rush to analyze, optimize, and solve every difficulty we encounter.

Sorrow and Pain

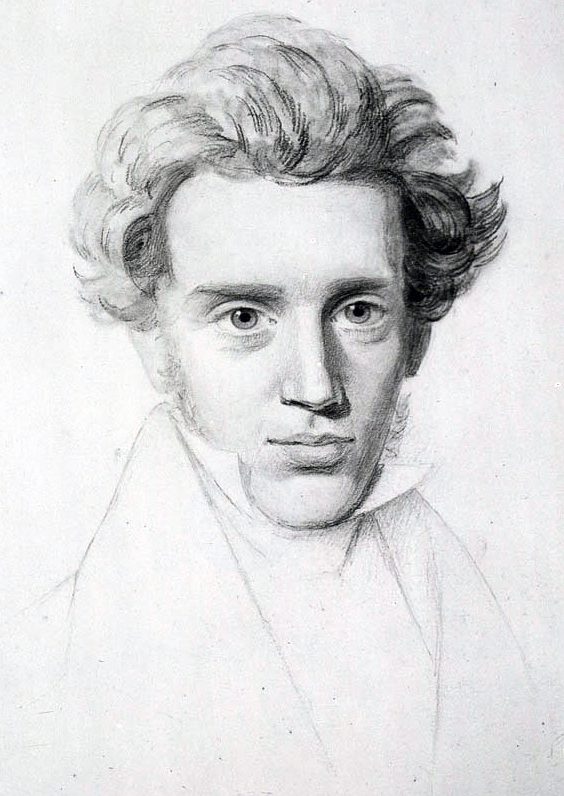

In Either/Or: A Fragment of Life, Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard distinguishes between two types of suffering: “sorrow” (sorg) and “pain” (smerte).

When we suffer in the modern world, we are most often experiencing pain, as it is a suffering that is accompanied by reflection. It is a subjective experience where we grapple with our suffering, asking questions like, “Why has this befallen me?” or “Why can it not be otherwise?” We are tormented by our own guilt, sense of responsibility, and subjective understanding of misfortune. This makes pain all the more acute.

However, sorrow is a far more substantial form of suffering. It is a state of being that is not yet fully reflected upon or assimilated by the individual. In Kierkegaard’s discussion of ancient tragedies, he argues that the hero’s sorrow is tied to their fate, a state of unalterable circumstance or a debt inherited from a previous generation. It is not a personal wound but an essential part of their being.

Of particular interest to Kierkegaard is Antigone, the protagonist of the final story in the Sophocles’ Oedipus trilogy.

Oedipus is best known for being abandoned by his father, Laius, the king of Thebes, after an oracle told him that his son was destined to kill his father and marry his mother. One of the king’s servants was commanded to abandon him on a mountain to die, but the servant pitied the child and instead gave him to a shepherd, who then gave him to the king and queen of Corinth, who raised him as their own. Years later, en route to Thebes, Oedipus accidentally struck Laius with a chariot, killing him.

When Oedipus arrived at Thebes, he discovered that the city was being terrorized by the Sphinx, a creature with the head of a woman and the body of a lion. Anybody who could not answer the Sphinx’s riddle was killed. Creon, Laius’s brother-in-law and acting regent of Thebes, proclaimed that whoever could defeat the Sphinx would be named the new king of Thebes and would be given the hand of queen Jocasta. Oedipus correctly answered the Sphinx’s riddle, and the Sphinx killed herself.

At the beginning of Oedipus Rex, the first drama in the Theban cycle, the city of Thebes is afflicted by a plague. Oedipus consults the oracle of Delphi, who informs him that the plague is the result of a great sin: the murder of the previous king, Laius. She adds that the murderer remains in Thebes.

Oedipus swears to find the murderer and banish them from the city. After investigating the circumstances of Laius’s death, Oedipus discovers the truth: he killed his father and married his biological mother. Horrified by this revelation, Jocasta hangs herself and Oedipus blinds himself. Moreover, Oedipus asks his father-in-law (and grandfather), Creon, to banish him from Thebes and watch over his daughters, Antigone and Ismene.

In Oedipus at Colonus, the disgraced king is accompanied by Antigone into exile. They seek refuge at a sacred grove near Athens, and the Athenian king, Theseus, takes pity on Oedipus and offers him protection.

Meanwhile, Oedipus’s sons, Eteocles and Polynices, have begun fighting for control of Thebes. They seek their father’s favor, as a prophecy states that the side which possesses Oedipus’s grave will win the war. Oedipus, however, curses both of his sons. He denounces them and prophecies that they will kill each other in battle. In the end, Oedipus disappears into the grove; only Theseus is witness to his burial site. The drama concludes with Antigone and Ismene departing for Thebes in hopes of preventing the war between their brothers.

In the final play, Antigone, Eteocles and Polynices have killed each other in battle, and Creon is now the king of Thebes. Creon decrees that Eteocles, who fought for the city, is to be given an honorable burial, while Polynices, who led an army against his own city, is declared a traitor and his body is left unburied and unmourned. Anyone who disobeys Creon’s edict is to be sentenced to death.

Antigone, the sister of both brothers, is horrified. She believes that divine law, which dictates that all people deserve a proper burial, is superior to any human laws. Antigone secretly performs a symbolic burial for Polynices, sprinkling dirt over his body. She is caught, and Creon condemns her to death by being sealed alive in a cave.

Had Antigone’s suffering been the result of Polynice’s symbolic burial, “Antigone would have ceased to be a Greek tragedy, it would be an altogether modern tragic subject.” Instead, Antigone’s own fate “is an echo of her father’s.” She is reaping what Oedipus and Laius had sowed long before. At the same time, both earlier generations were unable to avoid what had been prophesied in Delphi.

She embodies sorrow in its purest form. Kierkegaard goes so far as to call Antigone “the bride of sorrow,” as “[s]he consecrates her life to sorrow over her father’s destiny” and “her own.” She also cannot accept her brother being unburied, so she sorrows for Polynices as well. The guilt that Antigone carries is not her own: it is hereditary.

Yet, in spite of her suffering, Antigone welcomes the opportunity to be in service of the Fates. She does not push against her circumstances, and she does not dwell. She recognizes that things cannot be other than they are: Antigone will suffer, but she will not fight against the logos.

How different is she from us today? We reflect over every misstep, wondering how things might have had different outcomes. We regret that we were mistreated, or that we mistreated others. We seek ways of making amends, and they often fail. Instead of feeling sorrow, we feel pain. We can learn something from Antigone’s example–we are caught in the threads of fate, and no amount of reflection can change it.

The Joy of Eternal Recurrence

Fortunately, Friedrich Nietzsche offers us a way out of the cycle of ruminating pain. He believed that one of his greatest philosophical contributions was the concept of eternal recurrence. Eternal recurrence is the theory that every single thing that exists, and every single thing that has existed, and every single thing that will exist, has always existed.

Rather than seeing time as linear, Nietzsche views time as a perfect circle repeating over and over again.

We moderns have a progressive view of time: the past has led to the present, which will evolve into an as-yet-unforetold future. Those who view a progressive philosophy of history in ideological terms make two different arguments. The traditionalist–or conservative–argument is that the past was better than the present, and–as time passes–our conditions get worse. The modernist argument is that with each passing age is somehow better than the one that came before it.

Nietzsche’s philosophy of time is meant to push against the progressive perspectives that became widespread in the nineteenth century. However, he does not outline eternal recurrence as a factual description of how things are in the world. Rather, eternal recurrence is meant as a therapeutic tool that allows us to accept things as they are. Nietzsche’s philosophy is best characterized by the expression “Amor Fati“: Love of one’s fate.

In The Gay Science, Nietzsche writes:

I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who make things beautiful. Amor fati: let that be my love henceforth! I do not want to wage war against what is ugly. I do not want to accuse; I do not even want to accuse those who accuse. Looking away shall be my only negation. And all in all and on the whole: some day I wish to be only a Yes-sayer.

Nietzsche’s therapy is to find total acceptance in the universe. He is not the first philosopher to stumble upon this idea. The former Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, in his Meditations, pushes us to do the same. The primary difference between Nietzsche and the young emperor is that Marcus Aurelius inhabited a cosmology that took the existence of fate for granted. The logos was the universe’s indisputable organizing force. Nietzsche, on the other hand, must push against the atomistic individualism of free will and absolute personal responsibility.

Rather than demanding that we accept the logos, Nietzsche provides us with a thought experiment:

What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: ‘This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sign and everything unutterably small or great in your life will have to return to you, all in the same succession and sequence–even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned upside down again and again, and you with it, speck of dust!’

Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: ‘You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.’ If this thought gained possession of you, it would change you as you are or perhaps crush you. The question in each and every thing, ‘Do you desire this once more and innumerable times more?’ would lie upon your actions as the greatest weight. Or how well disposed would you have to become to yourself and to life to crave nothing more fervently than this ultimate eternal confirmation and seal?

Nietzsche’s role is to turn the modern tragic figure–he or she who experiences pain–into the classical tragic figure–that which experiences sorrow. While both are forms of suffering, the ancient hero can see the logos. Instead of questioning, we can come to accept. We, too, can transform suffering into joy.

How Fate Can Help Us

When we stop ruminating on the circumstances of our own lives, when we stop asking “why,” we can also come to accept our life circumstances. We find ourselves like Antigone: inheritors of many cycles of generational trauma, forms of violence far outside of our control, or recipients of a series of unfortunate events.

Even so, we are unable to control the chain of events that brought ourselves to these circumstances. In fact, we cannot even control our own actions: we are so conditioned by childhood upbringing, social dynamics, and structural issues that it is impossible to say where precisely our own agency lies.

Some find the possibility that they lack agency constraining–for those who feel this way, such possibilities make them feel like a puppet. But my contention is neither empirical nor factual. Instead, welcoming the idea of eternal recurrence into our own lives serves as a therapeutic tool, one that allows our anger to subside, our grief to settle, and our suffering to transform.

Both Kierkegaard and Nietzsche understood that the experience of suffering was qualitatively different for the ancients. They inhabited a world where fate was not a philosophical concept but a lived reality, where the logos provided structure rather than constriction. We cannot return to their cosmology, but we must learn from their approach: to find in acceptance the freedom that comes from no longer fighting the unchangeable, and discovering what emerges when we stop asking “why me?” and start asking “what now?”